Issue № 3

April 2014

Shards  Shardwrecks

Shardwrecks  Events

Events  Visions

Visions  Letters

Letters

August

February

March

April

If understanding nature was easy, the Forest Journal would not be needed. However, this aim conceals an irresolvable contradiction. Human beings love meaning. Nature does not need meaning.

The previous issue showed how cuts allow seeing nature. But cuts do not give meanings but intuitions, sensations, insights.

Meanings are another way to understand nature.

Shards come to the rescue.

Along the edges of the cuts, particles torn from nature are formed: a tree separated from the forest, an animal that has lost its flock.

People bring these gathered particles into their world, name them, search for meaning in them.

This is how shards are born.

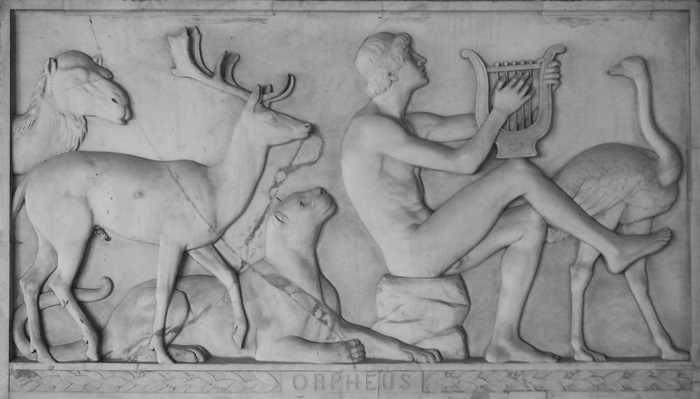

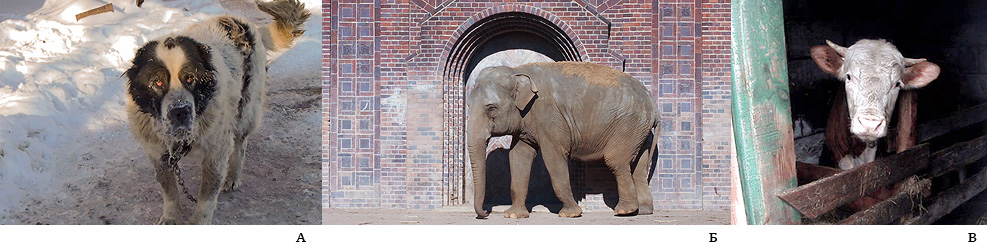

Examples of meanings in shards: A — friendly protection, Б — a clumsy miracle, В — a useful alliance.

To cover the whole of nature with meaning is like covering an ocean and, therefore, impossible. It is much easier to draw a relation with a nature shard of a size similar to ours.

The shard is a small window between nature and human beings, which is looked into from both sides.

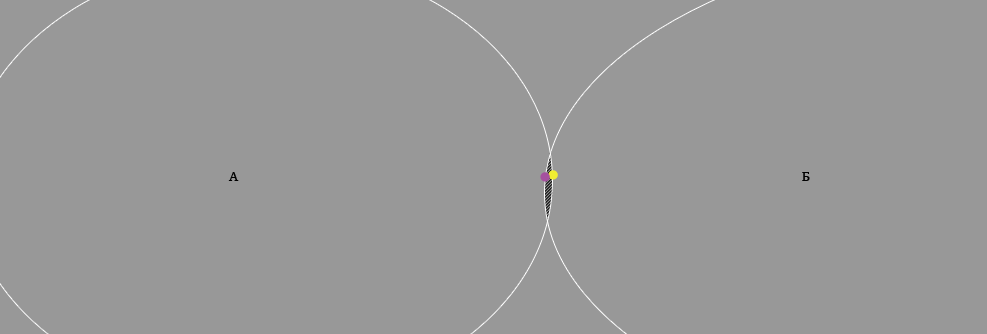

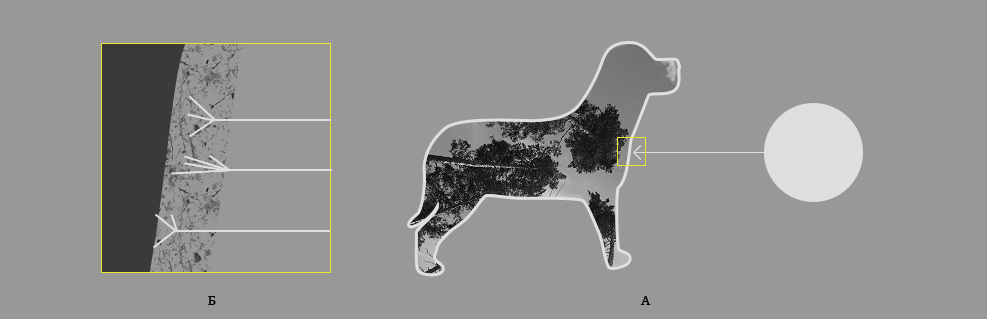

The intersection of the natural aggregate (A) and the human aggregate (Б) is shaded. Two creatures meet in this conflux.

Even such a small window into nature, like a shard, is often too dangerous for humans. This is a well into which feelings and meanings fall with frightening speed and irretrievability — without any use for learning.

In the case of most shards, this unfortunate failure is avoided due to the fact that a viscous membrane forms around them. Through it, a gaze, a word, or an experience of a human being infiltrate the shard more slowly, leaving a chance for acceptable meanings to emerge.

Functioning of the shard's membrane. A — is the human intention to understand the shard. Б — the intention is stuck in the membrane, keeping from slipping into the meaningless ocean.

Membranes are a characteristic feature of shards. They are as crucial to their description as shells are to mollusks.

Let's see what layers form membranes.

Name — without a name, there is no shard. The nameless shard is still part of nature. A shard marked with a name becomes separate, independent, unattached.

The shard's name reflects how it was removed from nature. On the left is the name of a single entity. On the right is the name of the overgrowth piece.

Care – the shards are always wrapped in care; otherwise, they would simply die outside their own world.

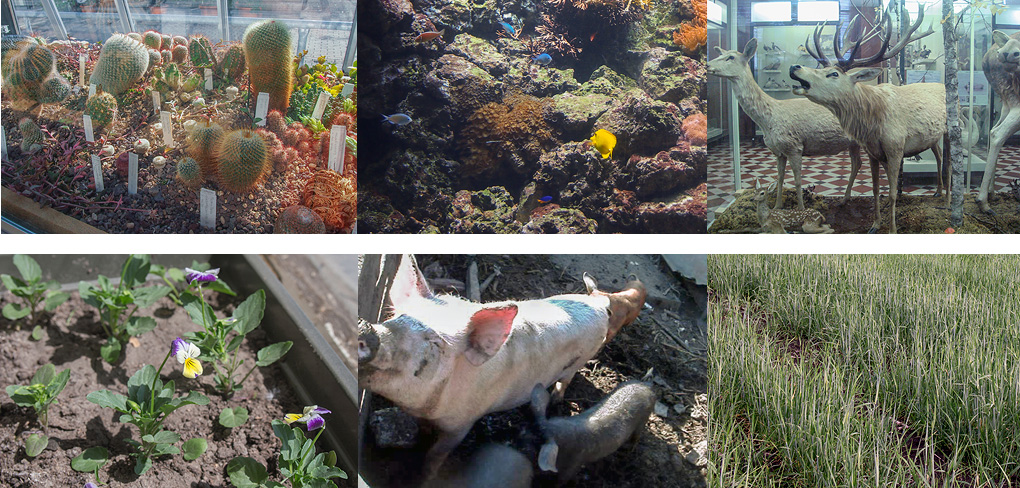

Examples of care wrapped around shards.

Knowledge – since the shard has a unique self, the membrane contains the traits of its essence.

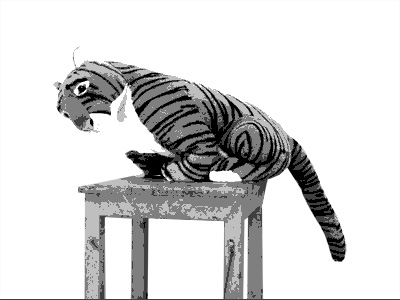

An example of knowledge in a membrane.

Despite their orphanhood, shards retain the desire to come together. Human beings respond to this impulse and help the shards.

They do this in two ways.

If the properties of the shard membrane come to the fore, then a collection is fetched. In the collection, all the features of the shards are emphasized and enhanced.

If one specific meaning is required from the shards — for example, usefulness — they are raised as an army.

In the top row are examples of shard collections, and in the bottom row are examples of armies.

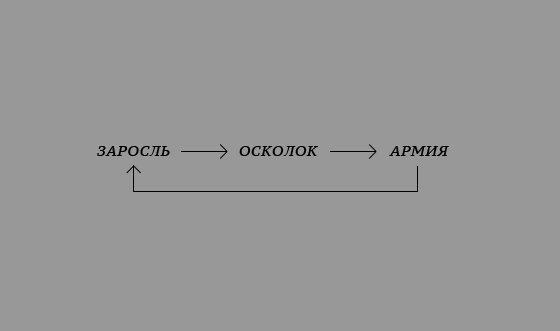

Sometimes in armies, the properties of the shards fade, the membrane weakens — and then the armies become overgrowths.

Thus the shards return to nature.

Overgrowth → Shard → Army ↺

It is easy to underestimate the membrane's contribution to the shards' existence. In fact, it is their critical vital organ. Let's study two examples of how the membrane's disintegration led to the shardwreck.

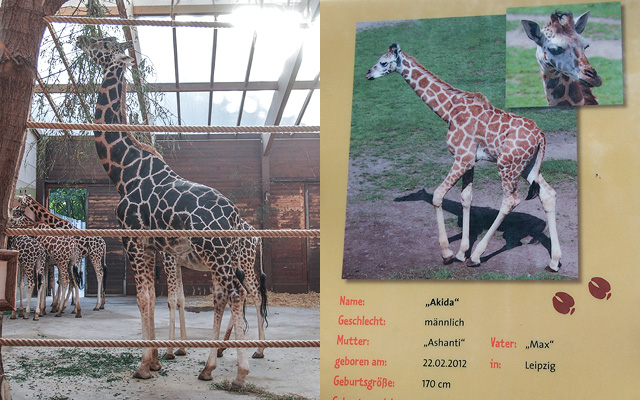

The first story happened recently — the murder of the giraffe Marius who lived in the zoo. A zoo animal is a typical case of a shard in a collection. Those animals have names, are taken care of, and are studied. Meaning and understanding of nature are extracted from them not by one or two but by dozens of people.

The zoo's incapacity to sustain the animal was a minor motive for Marius' slaughter. The main reason was the urge to model nature. An idiosyncratic understanding of the laws of nature and the ways of its functioning led to the idea of getting rid of the giraffe. The zoo's ambition was not only to understand nature but also to act like it; thus, the procedure, as well as the decision, became the demonstration and reenactment. It was beyond the capabilities of the shard membrane, meant for interaction, not protection.

Care component fell out of Marius's membrane — and the whole membrane collapsed. The humans of the planet were poured out with such an amount of nature that they did not intend and could not bear. The excess of nature turned into suffering.

Just one shardwreck due to the loss of the membrane led to deplorable consequences. The membranes not only allow us to commune with nature via shards. They also protect from the myriad forces that sweep away the human.

The second case occurred in British Columbia with Robert Franklin Leslie. The story is described in his book "The Bears and I". A young gold digger picked up three little orphaned bear cubs. He decided to take care of them, gave them names, and made friends. Contrary to all laws, he formed shards right inside nature.

The consequences were not long in coming. Nature rejected the fragments — a forest fire destroyed everything around the dwelling of Robert and the bears; the heroes barely escaped. In the new forest, they held out for another two years. Bears have become almost adults.

Two of them died. One by the hunters' hands. An old strong bear killed the second, who could not defend himself properly because of an injury done, again, by hunters. The third had to be sent to the most distant and inaccessible forest for salvation.

Unable to expel the shards, nature destroyed their membrane. The hunters weren't shooting at Rusty and Dusty but at two nameless beasts. The bear killed another bear because he didn't acknowledge the care.

The delicate cocoon around the animals vanished, and the nature rushing out of them caused grief again.

Scene from the movie based on the book.

The goldfish is remarkable for its outstanding capabilities to generate the most unpredictable monstrosities. Its deformities are characterized by the absence of any of the fins or, on the contrary, by their unusual extension, doubling or even tripling in quantity, then by a fantastic bulging of the eyes, giving them the appearance of some kind of cherries or binoculars, then by a terrible swelling of the body or head, then, finally, by the complete absence of scales.

N. F. Zolotnitsky "Amateur's Aquarium"

Shards, among other beautiful qualities, reveal the genuine desire of nature for freedom.

Breaking away from the steadfast overgrowths, where everyone watches over everyone, the shards begin to joyfully transform, playfully mutate, carelessly become dissimilar.

In shards, nature is freed from itself.

Freedom to nature!

Artist Ivan Gorshkov answers the question, “What is nature?”

Bring home a wild animal or plant. Take care of them, give them a name. Try to understand them.

Release back in habitat after a month.

Send observations of your guest and your own experiences to the Forest Journal.

Our reader wrotes:

Hello, I would like to share the first thought that arose after reading the second issue of your journal.

When the world was tight, and the exam was the most terrible trial of my life, I made cuts on myself several times. It wasn't a riot or a performance; it was a look inward through the outside. It was done not obviously — on the thigh, under the elbow, on the shoulder. Able or frightened, a sense of self-preservation crowned all sorts of arguments against. But interestingly, the process was more important than the outcome. Not anyone, but you, just like that, not with a purpose, totally without it.

It is more important to observe the ongoing gradual healing, how the skin pushes to its original shape, how it restores the damaged, scarring for sure. And tries to get back to normal.

Understanding that you are the source code for the system, an absolute sample - that's what I took out of my experiments then. Also, that I don't know what I really am.

If you think about it, the forest always tries to heal its cuts, gradually populating ravines and old paths. And later, at the site of the cut, we see scars and tireless healing work.

The absolute of the organism is wholeness.

FJ comment: in connection with this, the experiments of Hans Driesch, an embryologist of the early twentieth century, are recalled. Dividing the embryo of a sea urchin into two parts, he discovered that each of the halves, however, produces a complete sea urchin. The scientist believed this proves the body's desire for finality, the integral inner goal for the full realization.

We received a question:

I want to ask: can sparrows be considered winter birds and ravens off-season? And does watching them carry a hidden threat?

Thanks again for meeting with the wonderful; I wish you further creative success.

S.G.

There seem there are sparrows in the summer too. And watching something is always dangerous. Thoughtful and honest observation destroys the worldview.