Issue № 1

December 2013

The Journal  Overgrowth and Ripples

Overgrowth and Ripples  Events

Events  Disaster

Disaster  Atlas

Atlas

In his book Forest Journal, Soviet children’s writer Vitaly Bianchi was able to accurately capture nature’s essence. He described its ancient phenological cycles and the human cares associated with them (e.g., hunting). He talked about collective farm labor and animal life in the city. He assigned children natural history exercises that would prepare them for tending gardens and fighting pests.

Bianchi explained nature through its meanings, its aesthetic, moral, mundane, agricultural, and political significance. The moment of emergence he describes is the transition from Ivan Turgenev’s A Sportsman’s Sketches to Nikolai Vavilov’s Agroecological Survey of the Main Field Crops.

Bianchi's Forest Journal depicts nature as a fantastic maelstrom of creatures, from whales to the last ear of corn, a maelstrom rushing into the bottomless, insatiable mouths of Leningraders, predators, and death.

As the Soviet writer describes it, nature is a biomass incessantly devouring itself that promises its offspring only an absurd disappearance. And the historic milestone he records is the full-scale, planetary inclusion of man’s technological forces into this feast of self-absorption, increasing its speed many times over.

Time has passed, our minds and bodies have changed, and nature, whatever that means, should again be grasped and outlined. The new Forest Journal will try and answer a simple but vital question.

What is nature?

Can we understand nature? It is hard to understand a field of events that contains no ready meaning. It is the borderline of our outlook as human beings.

Can we come to know nature? We can hope for discrete insights.

What methods will the Forest Journal use to explore nature?

You can explore nature by becoming a mindless part of it, through seclusion and living in the wild, body pressed to body, and self-forgetting. These are good ways, but they won’t do for those seeking knowledge communicable to others. The illusion of spiritual understanding is also a danger. Art gives us a chance to work around both problems.

You can explore nature by using a language bereft of meanings but consonant with the reality we’re interested in, i.e., mathematics. But before we use mathematics, we should probably pose the same question to it that we pose to nature. People who resort to mathematics risk doubling their confusion. Derivatives of mathematical methods, such as pattern theory and fractals, promise considerable efficiency and pleasant insights. We can use them, but with great caution. The dubious capacity for explaining everything in the world forecloses any question as soon as it is raised.

No clear dangers are to be divined in other, less ambitious methods, such as contemplation, collecting and analyzing samples, sketchings, photo reports, articles, speculative imagination, and random readings of secondary sources. We can resort to them as often as we like.

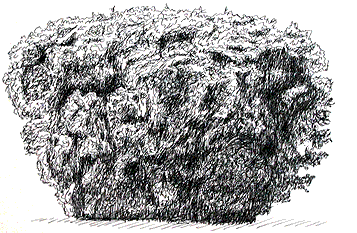

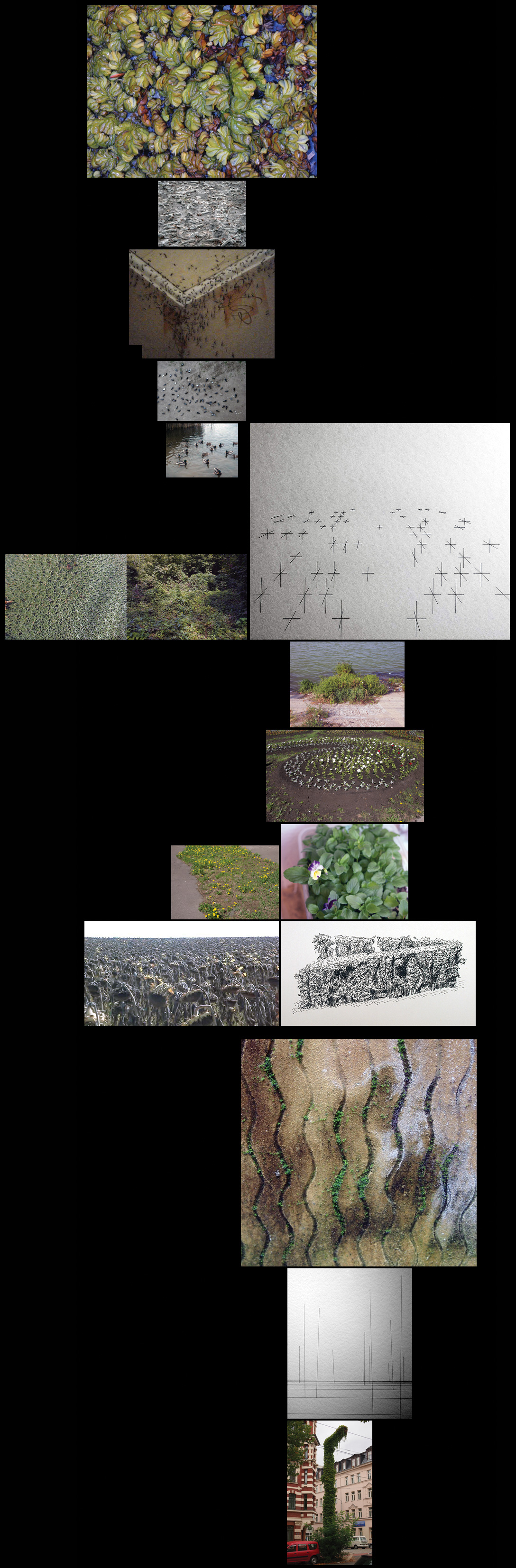

Example of a place in the process of overgrowing

Observation bears witness to the following. When nature occupies the spots it has found, it strives for uniformity, not variety, as is commonly believed. I will try and show how this happens and the outcomes it produces.

Nature’s desire to occupy spaces is so obvious, it does not require a detailed explanation. We should deem it a basic property, its principal means of existence. Wherever a spot has been found—a crack in the rocks, a broad valley, the roof of an old building—nature will be there.

Whereas initially its presence is chaotic, over time it strives to ever greater uniformity.

This process should be called Overgrowing. In fact, overgrowing requires no additional stimuli. If there is a spot and no hindrances are present, it will be overgrown.

OVERGROWTH is the outcome of overgrowing. A stand of growth is a place that has been uniformly filled by nature.

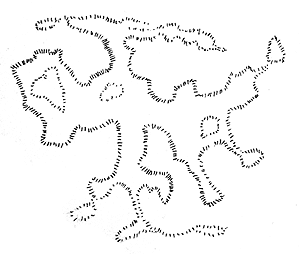

The two main features of overgrowth are the existence of borders and the lack of internal structure, i.e., uniformity. The boundaries of the overgrowth coincide completely with the boundaries of the place.

Nature pours overgrowth into a place the way water is poured into a pitcher. The water has borders, although there is no particular shell or membrane, no “boundary organ.” And the water is entirely identical at all points. Overgrowth is the same way.

Overgrowth and its defining properties: above, the border; below, internal homogenity

HUE

Let’s compares these two stands of overgrowth. One has a blue tint; the second is markedly white.

TEXTURE

The overgrowth on the left has a complex, folded texture; the brush on the right is velvety, almost smooth.

THICKNESS

The overgrowth on the left is thick, while the one on the right is thin, although the textures are similar.

MOBILITY

Depending on the nature of the place, overgrowth can be rooted (left) and nomadic (right).

The size of a stand of overgrowth is not so important, but of course boundless, endless stands of overgrowth occasion greater joy and excitement.

If we recall that overgrowing is nature’s principal aspiration, we can imagine that the object of its movement is for all the places filled by nature to unite and form a single stand of overgrowth.

Perfect stands of overgrowth begin to ripple.

Artist Alexey Buldakov answers the question, “What is nature?”

Nature is a disaster. The individual human mind tends to regard nature as a series of disasters, but it is really a single disaster, total and perpetual. This disaster is impossible to describe and predict, but you can observe it and partake of it.

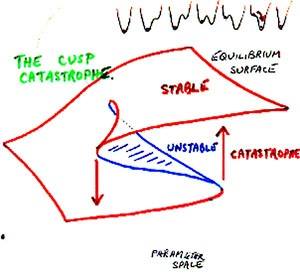

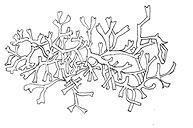

An illustration by René Thom from his book Structural Stability and Morphogenesis

I’ve always liked mistakes. They are like little disasters that can cause big ones. The mistakes that occur when you try and describe complex shapes, careless mistakes, the mistakes of Galileo and Kepler, and computer glitches. The effect produced on us by an inconsistency resulting from using values that differ from customary ones is what I call knowledge. First, the sensory experience of seeing the illusion of an integral worldview destroyed, and then the rational elimination of the mistake’s consequences: these are the components of experience. A mistake is like a crack in the pavement filled by sensory experience, by qualia. When we experience a mistake, we better understand nature. For example, when we make mathematical mistakes, we better understand the nature of numbers. Or, to put it more broadly, a language error leads to an understanding of the nature of communication.

Equation

The fluidity of watercolor makes it hard to control the shape. A disaster occurred during an attempt to paint a dove’s feathers.

Go to an aquarium store and buy a very small amount of floating crystalwort, a type of moss popular amongst aquarists.

At home, pour water into any wide container and put the crystalwort in it. Place it in a well-lighted place, such as on a desk under a lamp.

Watch the overgrowth taking place. When there is a lot of crystalwort, move it to a differently shaped container. Watch as the plant fills up the new place. Write down your observations and send them to the Forest Journal.

“All the Plantae Kingdom will appear again in front of us as immense ocean”

Goethe