Issue № 7

October 2015

Compass  Events

Events  A Weak Shiver

A Weak Shiver  One Interaction

One Interaction

«Compass» — an observation by Lisa Konovalova.

December 2014

In late autumn, I went to the forest for a purpose: to gather a sack of dry ferns. Nights were frosty already, and white glaze covered the fallen needles. The morning sun shone with low, amber light. The forest was still: no birds, no insects, no wind, no movement.

Across the barely notable path lay a shaggy, old, brown cat in winter fur. She looked weak and irritated; I thought she came from the neighboring village to die. On the way back, she was gone.

Cat's ghost did not disturb the wood's serenity in the slightest.

Then two fuzzy dark shapes materialized. They flashed like giant sphinx moths somewhere on the side, in the tall old pines. Their flight emitted something, not a noise, but a mute hoot.

They were two large woodpeckers, completely black, with a red comb. The pair flew through the transparent November forest and spiraled around the oaks; they were peaceful and the only beings in this empty overgrowth.

Why did they enlace quiet oaks and pines with an invisible net of their movements? Why were they staring at each other's large yellow eyes so insistently?

There will be sounds in any similar autumn forest if there is wind. Large and frail trees will begin to sway unevenly and creak. Or one of them will crash on the other's brunches, and then both will creak. A caring roll call. Would they like to become a windfall and, finally, rest together?

Steppe grasses do this in autumn: become dry and lie down, cover each other, intertwine, freeze.

Reeds and sea buckthorn grow in Patagonia, and the heavy wind is frequent there too. I pushed toward the water, and a cobweb blocked my path. It linked two dry reed stalks, violently and chaotically thrust by the wind. The web rushed along with the stems, keeping them bound effortlessly.

A spider made a netting between huge granite stones on the shore. He tied heavy pieces of matter with delicate threads and was proud of himself. The spider desired more ties to happen, waiting patiently in the crevice.

In autumn, you can find tufts of fluff or cobwebs in high, thorny weeds. It is never clear whose it is — plants or animals. Is it seeds or cocoons. Did they originate here, or the air carried them.

Delicate threads move through the overgrowth, binding its elements here and there, then disperse and migrate somewhere else.

And sometimes, you can find foam or a lump of slime.

A weak shiver runs through the overgrowths.

A network of the tiniest, faintest touches of various creatures flashes, flickers, and pulsates in waves.

A blade of grass clings with its tendril to another blade of grass. The pines lean towards each other invitingly. The leaf is torn off and descends to other leaves. From above, from distant branches, fine droplets of moisture fall on the face, vanishing a moment before touching the skin. A bee fumbles in a tangled orb of small flowers, and a large and bright flower, shining in tall grass and shrubs, deliberately strikes the sight.

A weak shiver happens quietly and imperceptibly, hustling to dissolve in the parental overgrowth as soon as possible.

Some beings assist a shiver in happening. They mark channels and paths along which a weak shiver will glimpse like a spark.

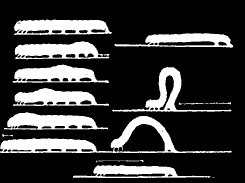

Such are snakes, caterpillars, slugs, and others having long sinuous bodies that move like a wave. Sometimes they leave a visible trace of their work — lines in the sand, a streak of mucus, a web thread.

Cutting a reed stalk, I disturbed the nest of several dozen tiny worms. They spilled out of their shelter, trembling in their little bodies. I imagined their life here, in the wriggling darkness, together.

A shiver, like a lightning bolt, needs a pre-drawn route. Its weakness needs assistance.

We sat near the water and watched the dry branch performance. It danced on the waves amusingly, arching its round back up and down.

Another time the wind brought a yellow aspen leaf and threw it into the still water of the shallow bay. The water surface was covered with fine, intricate ripples. Along with these, the leaf moved up and down, arched, and spun.

The action of waves of water or wind pushes the most diverse pieces of overgrowths to display their ability to shiver. This ability is characteristic of almost all of them, even the plainest. Some innate organ is ready to respond with trembling to the slightest impulse from outside.

When the pristine and solid overgrowth is agitated, a weak shiver may creep through it. The tissue of the overgrowth is changing: empty nooks and meanders appear through which beings can notice each other.

If the whole forest is filled with yellow-purple blankets of blooming cow-wheat, and inside them, bees, bumblebees, and hoverflies grumble deeply, it is effortless to decide that there is nothing stronger than their radiant bond.

And it is so different when a late white flower bloomed for some reason on a gloomy day, and a slim, chilled mosquito swooned inside it.

A weak shiver may seem not at all weak, quiet, and sparse but, on the contrary: robust, sonorous, and integral. It is easy to get rid of this delusion — compare overgrowths' size and weight, their strength and confidence, their indivertible flow and stillness, their clear boundaries and inner purity — compare all this with the smallest shudders of a flower and a bee, a fallen pine needle, a bird giving a voice — to understand:

the shiver is weak, quiet, and sparse.

It needs help:

1) The agitation running through an overgrowth,

2) The path drawn by a snake,

3) The daring call of a flower.

In one ancient spruce forest, dark and swampy, heavy black ants live, and round, gloomy birdies hide.

Birdies can suddenly fly out straight from under your feet, patiently lurking in a dense high fern. The dense beating of their short, opaque wings is a flash of lightning-fast shiver.

Ants occupy all the rest of the forest.

They cross streams on fallen logs, lay reasonable roads from one huge anthill to another, they walk through spruces, mushrooms, and moss: not a single part of the forest remained without their black step.

Do the ants want to bind the whole forest with a trembling rustle? Do they hope that their shivering will become vigorous and stable? Is this why they build their anthills, in which they sovereignly order any needle, any step? Are they their own wave and shiver?

Two months pass, and the ants are gone; anthills — large, damp, warm, motionless — leaned against the spruce trees.

A frog sits on the bank of a brook.

The brook is fast, shallow, and translucent; pebbles and sun glares are at the bottom; ripples, water striders, and sun glares are above. A heap of trembling sparks!

The frog sits in the moss at the roots of the tree. Everything is motionless: the tree, the moss, and the frog — not a single swaying. Only the neck shivers, often-often — this is how the frog breathes.

The frog, like ants, also wants to keep the shiver and carry it inside for as long as possible? Is it afraid to move lest the faint beating go out?

Probably, the moss scared the animal.

For those who are also afraid of moss, a wise children's rule will help: if a tree creaks in the forest, you should politely answer "Hi".

A nest of worms, a leaf on the water swell, swallows splashing in the wind, a flower reaching from afar.

The weak shiver begins where the wave has passed. It ties, for a glimpse, beings leaning toward each other and disperses when the overgrowth straightens and takes its place.

The best observable instance of the weak shiver is the crawling caterpillar.

What I'm thinking about is why does the weak shiver, in whatever form, so gently and directly attract the gaze and soul of a human being?

It is sometimes believed that the tiniest drops, hoarding countless periods, can one day turn into an irresistible force.

So, one summer evening, black forest ants will finish their rustling labor and set the overgrowth aflame with a dazzling shiver.

A Weak Interaction Experience by Anastasia Tailakova.

Dear Forest Journal, this is your devoted reader Sasha writing to you. I would like to tell you about how I made a real friend among the plants. Where I live, I rarely get to meet nature, but recently I visited a magical place filled with rustling grasses. While walking along the chalk roads, I met the Spiny Life Form; we immediately liked each other and decided to continue the journey together. The Spiny Life Form (or simply Spine, as her friends call her for short) is very light and risked flying away with the wind and getting lost at any moment, but I held her tightly and protected her from danger. We went down the hill and met a couple more plants; we were introduced to each other, but unfortunately, I did not remember their names since our acquaintance was rather brief. Later, I introduced the Spiny Life Form to Ghost Horse Backbone, with whom I had become friends a little earlier. Soon I had to leave the Land of Rustling Grasses, I took the Spiny Life Form and Ghost Horse Backbone with me, and we set off. Many dangers awaited us: the tumult of cities, the roar of trains, and human cruelty, but we steadfastly endured everything and reached a calm place. In the evenings, the Spiny Life Form whispers tales of boundless lands to me, and I listen carefully, trying not to forget anything.

You need to find something shivering. And try to make the shiver last as long as possible.

Sketch a diagram of how the shiver fades. Send it to the Forest Journal.